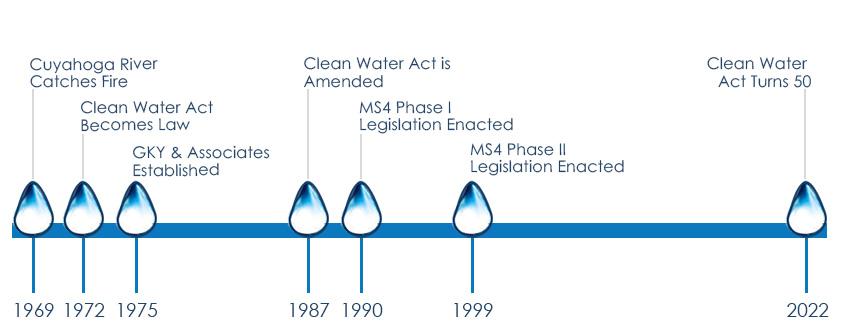

October 18, 2022, marks the 50th anniversary of the passage of 33 U.S.C. §1251 et seq. (1972), which is commonly known as the Clean Water Act (CWA). The legislation amended the existing Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 to create a framework for regulating the release of pollutants into waters and regulating quality standards for streams, rivers, lakes, estuaries, coastal waters, and wetlands, which are termed “surface waters” in the legislation. As one of Virginia’s largest consulting groups dedicated to water resources and environmental sciences and a firm that is nearly as old as the CWA itself, GKY & Associates has been on the front lines of the implementation of the policy and programming spawned by the Act. GKY’s senior management reflect on their experiences and the next set of water quality challenges facing the US.

The Clean Water Act of 1972

The CWA was signed into law just three years after one of the most well-known ecological disasters in US history: the Cuyahoga River Fire in Cleveland, Ohio. While the June 22, 1969, fire was not the first instance of the river igniting— historians cite at least a dozen prior blazes—it was the one that grabbed media attention. The ensuing public outcry motivated lawmakers and environmentalists to change America’s relationship with our surface waters. Carl Stokes, then mayor of Cleveland, responded by championing pollution control legislation. He, along with his brother, US Representative Louis Stokes, advocated for increased federal direction and oversight of pollution control. Their advocacy, combined with the national environmental movement, led to the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972.

Per epa.gov, the CWA did the following:

- “Established the basic structure for regulating pollutant discharges into the waters of the United States.

- Gave the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to implement pollution control programs such as setting wastewater standards for industry.

- Maintained existing requirements to set water quality standards for all contaminants in surface waters.

- Funded the construction of sewage treatment plants under the construction grants program.

- Recognized the need for planning to address the critical problems posed by nonpoint source pollution.

- Made it unlawful for any person to discharge any pollutant from a point source into navigable waters unless a permit was obtained under its provisions.”

The permits required to legally discharge pollutants from a point source, such as an industrial or agricultural facility, municipal sewer system, or government installation, are called National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits. In most states, these permits are issued by a state agency, such as a Department of Environmental Quality or Department of Natural Resources. NPDES permits can incorporate limits for the amounts of specific pollutants that may be discharged, known as Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) and often identify Best Management Practices (BMPs), such as installing a screen on a water pipe to filter out debris before it enters the waterway.

Municipal Separate Stormwater System (MS4) Permits

The NPDES program did not, initially, include what was traditionally considered nonpoint sources of pollution, such as stormwater runoff. However, a lawsuit from environmental groups contended that stormwater runoff should be covered, an assertion that was upheld by the court system. At the same time the EPA’s own research indicated that stormwater runoff was a significant source of pollution. The court ruling and the research findings prompted Congress to amend the CWA with the Water Quality Act of 1987, which defined industrial and municipal stormwater discharges as point source pollution and requiring owners / operators to obtain NPDES permits. Permit requirements for municipal separate stormwater systems (MS4s) were implemented in two phases: Phase I for medium and large cities and certain counties with populations of 100,000 or more and Phase II for small MS4s in urban areas as well as such institutions as public universities, hospitals, and departments of transportation.

GKY, A Water Resources Engineering Firm, Is Born

GKY was founded just three years after the passage of the CWA, giving the company and its senior management firsthand knowledge of and experience with many of the major milestones described above. Today, GKY’s engineers and scientists offer specialized expertise to MS4 permit holders and other entities that are interested in water quality, drainage, flood control, and related issues, primarily in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Throughout 47 years in business, its service offerings and customer base have been closely tied to the Act’s implementation, with the firm both responding to the demands of the water resources industry and driving best practices and emerging technologies. GKY and several of its senior leaders, who entered the industry in the 1980s and 1990s, have seen the programs and policy associated with the CWA evolve. They see, in GKY’s day to day work, the impact that it has had on watersheds and waterways, including the Chesapeake Bay, the health of which, the standards and regulations across much of Virginia seek to protect. They shared their perspectives on what things looked like when they entered the industry, how things are today, and what the future may hold.

The Early Years of The Clean Water Act

Like GKY itself, Senior Water Resources Planner Doug Fritz, CPESC, began working in the water resources field prior to the CWA amendment that required NPDES permits for municipal stormwater systems. He says, “When I finished grad school and began work, stormwater was not an issue. NPDES [permitting] was strictly point-source and we were taught how to calculate in-stream mixing zones for the pollutant discharges. The other major concern at the time was wetlands protection.”

GKY Director of Water Resources Policy, Doug Moseley, AICP, CFM, agrees, noting that the concern for water quality has moved from primarily being the province of scientists and policymakers to local governments. “When I entered the water resources field, I began working for the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation as a Commonwealth’s Floodplain Management Planner, so my water resources perspective was initially formed around flooding and water quantity management, and not water quality. When I started consulting in 2000, I could see the water resources field evolving — on water quality — away from the specialty science-based studies primarily funded by EPA to a municipally-focused, practice-based industry working to help localities comply with the water quality measures included in the CWA.”

The Clean Water Act Becomes Local, Personal

With the local government involvement resulting from the MS4 permit system, water quality concerns have become more visible to the average citizen. This is due in part to municipal public information campaigns, such as those that warn against dumping into storm sewers, the visibility of various ecosystem restoration projects that protect water quality and enhance habitat, and the creation of Stormwater Utilities. Stormwater Utilities fund stormwater management infrastructure improvements via fees collected from property owners, usually based upon the size and type of property.

Moseley continued, “I think the biggest progress indicator that has emerged since the CWA is overall awareness, and the associated shift in outlook that no longer seems as tolerant of blatant water quality abuses. Municipalities, and their residents and constituents have learned a great deal about the value of water quality. It is now a quality-of-life metric for many communities. As climate change continues to reshape our outlook on natural resources, the importance of freshwater resources will only continue to grow.”

Brice Kutch, PE, GKY Senior Design Engineer, made a similar observation, noting that CWA compliance is no longer an afterthought on engineering and construction projects, “It seems in the forefront of many projects now, whereas it used to be secondary or tertiary.”

The Next Big Water Quality Challenge

When asked about the challenges on the horizon, Moseley said “Unfortunately, we have several from which to choose. I think the biggest challenge we face in the Chesapeake Bay region is how best to account for climate change and the shift we’ve seen in rainfall intensity, duration, and frequency (IDF) curves, and how that impacts on-the-ground decision-making for water quality and quantity management. Adjustments to local rainfall patterns impact water quality calculations. This, in turn, affects the performance of billions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure put in place to enhance water quality, but designed and built based upon rainfall patterns that are growing more obsolete as time moves forward.” To respond to this challenge, he says, we need to reexamine the frequency with which we update the rainfall data that is the basis for infrastructure designs. “The introduction of updated rainfall data, and more frequent updates to that data, may help decision-makers adjust strategies on the ground in a timelier fashion. We may always be chasing the standard we need, but we may be able to shorten the chase with more flexible standards based on best – and latest – available data.”

Kutch cited climate change as well: “The next big water quality challenge I see the US facing is repairing, replacing, and improving infrastructure to deal with climate change, more flooding, and larger rainfall totals.”

Fritz sees challenges on the legal front: “Environmental regulations tend to swing back and forth like a pendulum. It is likely that the next big water quality challenge involves restrictions on the applicability of the CWA resulting from court challenges.” Indeed, such a legal challenge has come forth in the form of Sackett vs EPA, opening arguments on which began October 3, 2022. At issue is the definition of “waters of the US,” a designation, under which, those seeking to develop adjacent land are required to obtain a permit. A ruling in favor of the plaintiffs could reduce the scope of the EPA’s authority to regulate wetlands.

The Impact on the River That Started It All

And what has become of the river that moved lawmakers to take action on water quality? It is today an American Heritage River, in honor of its role in the history of the US environmental movement. And while its health is substantially better than it was in 1969, it still has far to go. In July 2021, the EPA removed one of the Cuyahoga’s beneficial use impairments, that of eutrophication from stormwater runoff. Eutrophication results from excess nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, entering a body of water and creating an environment that encourages the growth of algae. Left unchecked, the algae deprive aquatic life of the oxygen it needs to survive. This is the fourth impairment to be removed, with six remaining. Because of these impairments, the Cuyahoga River remains a Great Lakes Area of Concern.

Learn More

To learn more about GKY’s technical, policy, and environmental solutions for water resources, contact us today.